Articles & Resources

January is for Warm Soups!

Well, winter certainly has us in its grip. The "holidays" have come and gone. It is easy to fall into the doldrums in January. I think January is the hardest month for me on the farm. Work wise, it is not the busiest. Sheep are all at the barn --no daily fence moves. Breeding season has ended, which means less barn work as breeding groups have been broken down and we are back to two main barn groups. There is no fence maintenance and no garden work. You might think I am on holiday! Haha. There may be less outdoor physical work, yes, but there is still plenty to be done. Lots of desk work: grant applications, planning for changes in infrastructure, mobile shade shelter planning, figuring out how to complete silvo-pasture projects, sheep registrations, etc, etc. A welcome distraction comes in the form of our farmer type annual meetings and grazing conferences— most of which happen over winter, as most farmers are on a bit of "down-time" or at least a bit more flexible schedule. Gathering with fellow farmers can really give you a lift out of the January doldrums; I really enjoy these opportunities to further community building while learning ways to improve what we do here on the farm. Ok, so January is for "hygge": finding joy in simple, cozy moments, emphasizing warmth, comfort, contentment, and togetherness, often through creating a pleasant atmosphere with good company (or quiet solitude), comfort food/drinks, and relaxation, fostering well-being and happiness. It's about being present, slowing down, and appreciating life's quieter pleasures, translating to coziness, charm, and conviviality. Sitting by the wood stove with a warm bowl of soup after morning barn chores is one of my favorite ways to find joy in January. I hope you all are well and finding your own hygge this winter. I leave you with a wonderful recipe for an Icelandic lamb soup. I copied it directly from the Icelandic Lamb website, which has a multitude of fabulous recipes. Be well and eat lots of good, local food. Icelandic lamb soup „Kjötsúpa“ Ingredients 850 gr / 30 oz of bone in pieces of lamb, preferably from the forequarter. 1,8 l. / 61 fl. oz. water 50 gr. / 2 oz. Pearl barley 8 pcs. Medium size potatoes 1 pcs. Rutabaga 6 pcs. Medium size carrots 4 oz. White cabbage 2-3 leaves dried Lovage Icelandic Sea salt flakes White pepper Place the lamb and water in a pot and bring to a boil on medium heat. Start prepping the vegetables by peeling and cutting the potatoes, Rutabaga, Carrots- and cabbage. Rustic cut works just fine in this case. When boiling point is reached start skimming for fat and any froth that rises to the surface, a slow simmer is preferable throughout the cooking time. Continue skimming 2-3 times for the first 20 minutes. Add the potatoes, barley and carrots and cook for another 10 minutes. Add the cabbage, rutabaga and lovage and continue simmering for 30 minutes. Season with salt and pepper and serve in large bowls.

Judging info The sires are evaluated and judged according to FAI judging standards. Points are given for individual body parts in following order: Points: Head - neck and shoulders - chest and conformation - back - loin - gigot - wool - feets - harmony. Score of 80,0 points is good for breeding ram and 85,0 points can be considered as excellent. Ultrasound: Ultrasound measure of eye muscle thickness in mm and of back fat in mm - eye muscle shape score (1-5). (H) Dutch ultrasound scanner, the type used by SOUTHAGRI. (S) Scottish ultrasound scanner - which measures about 2mm lesser eye muscle thickness than the Dutch scanner. This difference is not corrected in individual figures. Eye muscle shape: In autumn 1999 eye muscle shape grading started. The grading of the eye muscle describes how well the muscle keeps it´s thickness out over the backbone. The shape is graded from 1 to 5. The scale is following: 1. Poorly shaped eye muscle. 2. Fairly shaped eye muscle. 3. Adequately shaped eyemuscle.. 4. Well shaped eye muscle. 5. Excellently shaped eye muscle. Basic dictionary Basic dictionary for the printed version of Southram's sire catalogue which is in Icelandic. Here you can find translation and/or explanation of the tables and graphs in the sire list. Lambhrútaskoðun: Evaluation of ram progenies performed in September/October. Following items refers to the evaluation of the rams progenies: Fjöldi: Number of evaluated ram lambs Þungi: Average weight of evaluated ram lambs Fótleggur: Average canon bone length of evaluated ram lambs Læri: Average score for gigot muscling (highest possible score is 20, 16 is good, 17 is very good, 18 is excellent) Ull: Average score for wool (8,0 refers to good wool quality and no tan fibers) Ómvöðvi: Average thickness (depth) of the eye muscle in mm Ómfita: Average fat thickness on the eye muscle in mm Lögun: Average score for eye muscle shape (1 is poorly shaped muscle and 5 is excellently shaped muscle) Following explanations refer to the graph for each ram. Kynbótamat: Breeding value index (based on information from the sheep recording in Iceland. 100 is average) Gerð: Meat qualities based on the carcass grading Fita: Leanness based on carcass grading Kjötgæði: Meat quality index (MQI), calculated from meat qualities (40%) and leanness (60%) Frjósemi: Prolificacy of the daughters (for the young rams with few daughter records this index is mostly based on pedigree) Mjólkurlagni: Milking abilities of the daughters (for the young rams with few daughter records this index is mostly based on pedigree) Explanation of measurements & scoring Generally data gathered on the rams is done in Iceland, in the fall, when they are around 18 months. The data on the Icelandic Rams is then given in the following major categories: 1) Rams Name, Number, and Parents 2) Body Measurements- Weight and Lengths 3) Score 4) Ram Description 5) Production Results Explanation 1) Rams Name, Number, and Parents The rams are numbered as follows: The first two numbers in the ID number refer to the birth year of that ram. Thettir, # 91-931 was born in 1991. 2) Body Measurements- Weight and Length Measure: Weight and measure is in the same sequence for every ram. There are four numbers given here representing- Weight of the ram- A heavier the ram usually correlates to bigger, growthier offspring. Chest Circumference- A measurement of body depth. Width of Rack- The wider the rack, the greater the yield from this choice cut. Cannon Bone (front leg) Length- A shorter cannon bone correlates with a meatier, faster finishing market lamb.

“Whole Sheep, Whole Farm” (Wholesome Demand)

Grazing Grazing is the use of grasses and other plants to feed herbivores, such as sheep and goats. Most sheep and goats graze at least a portion of the year. On this page, grazing links are arranged by subject category: controlled grazing , extending the grazing season , grazing behavior , grazing management , grazing systems , management-intensive grazing , multispecies grazing , prescribed grazing , riparian grazing , rotational grazing , silvopasture , and stocking rates . KIND HORN FARM RECOMMENDS For optimal parasite management, we recommend that you keep your Icelandics in the same paddock for no more than 5 days at a time, with 1-3 days being optimal for the forage. Rest the pasture for 90 days ideally before bringing the sheep back for another grazing. Try your best to work within these guidelines! [PDF] Grazing Alfalfa - University of Kentucky Controlled Grazing Controlled Grazing of Virginia's Pastures Creep Grazing Extending the Grazing Season [PDF] Extending grazing and reducing stored feed needs - MW Forage [PDF] Grazing corn: an option for extending... - University of Kentucky [PDF] Supplemental pastures for sheep - University of Nebraska Grazing Behavior [PDF] Diet selection and grazing behavior - University of Maine Grazing Management Grazing Systems Grazing systems - McGill University Management-Intensive Grazing (MIG) Multispecies Grazing Prescribed Grazing Riparian Grazing Rotational Grazing Silvopasture Stocking Rates The Maryland Small Ruminant Page [sheepandgoat.com] was created in 1998 as an information portal for sheep and goat producers and anyone else interested in small ruminant production. The web site includes original documents and images as well as a comprehensive list of links pertaining to small ruminants and related topics. The web site was developed and is maintained by Susan Schoenian, Extension Sheep & Goat Specialist at the University of Maryland's Western Maryland Research & Education Center. Susan has been with University of Maryland Extension since 1988. She holds B.S. and M.S. degrees in Animal Science from Virginia Tech and Montana State University, respectively, and also attended The Ohio State University. Susan conducts the Western Maryland Pasture-Based Meat Goat Performance Test at her research facility in Keedysville. She raises registered and commercial Katahdin sheep on her small farm called The Baalands in Clear Spring, Maryland. Please direct all questions, comments, or suggestions to Susan at sschoen@umd.edu Disclaimer : The information and links contained on the Maryland Small Ruminant Page [sheepandgoat.com] and other pages created by Susan Schoenian are for informational purposes only and do not constitute an endorsement of any person, organization, business, product, or web site. The author disclaims any liability in connection with the use of this information. Users of this web site and all external links are advised to apply common sense and sound judgement to all information obtained from the internet, regardless of source. Last updated 01-Dec-2010 by Susan Schoenian.

This article first appeared in Sheep! Magazine. www.sheepmagazine.com

O.K. Now you have put down your deposit on on your beautiful new starter flock of Icelandic sheep. But, all of a sudden you have a million questions about what you will need to keep your new flock. I will try to summarize here what I feel are the essentials for getting started. You will certainly collect more tools and equipment, etc. along the way, but having some basics on hand will make the job easier. My article assumes that you have you r shelter and barnyard fencing t ogether, but if not, click on the highlighted links for each. Two things I would like to note here: 1) Icelandic sheep should have access to the outdoors all of the time, so total confinement is not an option in my opinion. 2) I would strongly encourage people to do barnyard fencing with woven wire. All right, now on to the basics. Books: These are some of my favorites. Storey's Guide to Raising Sheep - Paula Simmons and Carol Ekarius Managing Your Ewe - Laura Lawson The Sheep Book - Ron Parker Living with Sheep - Chuck Wooster The Complete Herbal Handbook for Farm and Stable - Juliette de Bairacli Levy Lamb Problems - Laura Lawson Feeding and Watering Many options should be available at your local feed stores. Buckets: We have quite a few different sizes and shapes of bucket and pails on hand. My favorites are the heavy duty rubber buckets. These are the ones that we use for water all year long, summer and winter. Since we don't use heaters in the winter, we have iced up water buckets twice a day. The heavy rubber buckets are the only ones that will hold up to smashing ice out of them. They last forever. We use the flatter, handleless variety for water. We also have several of the plastic variety with handles on hand. These are useful for giving water in the jugs. They also make a loud noise when you shake grain around in them -- sometimes you need to convince these sheep to do what you want. Pans: Again, what I like for pans are the heavy duty rubber ones. I have several of these on hand in different sizes for feeding minerals and grain to individual sheep -- mamas who have just lambed, or possibly a sick sheep who needs some extra nourishment. Feeders: Hay feeders come in many different shapes and sizes. You can buy feeders or make your own. All of the sheep equipment suppliers (see links on my resources page) offer many choices of metal feeders. We make our own feeders here using wooden frames and hog panel sections cut to size. We use a modified version of a Premier feeder. You can purchase a booklet of feeder plans for $3.00 from Premier, or they will send it for free if you buy panels from them. Whatever you choose for feeders, just make sure that you have adequate feeder space for sheep during the winter. Pregnant ewes and ewe lambs a minimum of 16-18 inches each of feeder space, if all of the ewes are to eat at once. I would rather see close to 24 inches per ewe, so that the more timid ones will feel more comfortable getting a space at the feeder. Waterers: Again, many different types of waters are available. We don't use any type of automatic waterer. Just the good, old-fashioned system of carrying water. I would love to have a nice set up with piped water all over the fields, big water trough with float valve, etc., but what I have right now works just fine. With the big rubber buckets, we change water twice a day. I really emphasize changing the water and cleaning the bucket out twice a day in summer. Germs can really multiply quickly with the warm summer weather, so scrubbing the edges of the water bucket is a wise idea. Mineral Feeders: Sheep need constant (daily) free-choice access to loose minerals. We also like to offer kelp for the trace minerals, and the sheep love it. We use a Sydell mineral feeder that is covered and rotates to keep the moisture out. This is what we use during the grazing season and move it from paddock to paddock. During the winter, we use simple (and cheap) plastic wall mount mineral feeders. We have the ones with two bins, so that we can put out the kelp and mineral mix side by side. Just be sure to situate your mineral feeders so that blowing rain or snow will not ruin the minerals. Galvanized Storage Cans: Pick up several of these. We have a bunch of these cans lined up and labelled with mineral mix, grain, alfalfa pellets, kelp, etc. They keep contents fresh and critters out. Equipment A few things I would recommend to start out with. Panels: Having 4 -6 panels on hand to start with will serve you well. They are so helpful for squeezing sheep into a small space when you need to work with them. And 4-6 panels can make up to 3 lambing jugs if you start with a corner and stay along the wall. We have metal panels that hook together, but one could easily make wooden panels. All of the major sheep equipment suppliers have lovely metal panels that hook together nicely at the corners. I like the ones that are 5 feet long by 40 inches tall. Sheep chair: Not absolutely necessary to have on hand from the beginning, but if you can afford one....get it. These chairs will make the job of trimming hooves much easier. Tool box: A medium sized tool box comes in handy for toting around "first aid" stuff and medicines. Pitch fork and dung fork: You will need these. One for clean hay, the other for moving dirty bedding. Small stuff Hoof Trimming Shears: These come in different sizes. Female shepherds should look for smaller sized trimmers. Drenching Gun: For administering oral liquid medicines. You can find these in any of the supply magazines, or possibly at the feed store locally. Scale: We use two scales, one for weighing lambs and the other for weighing our skirted fleeces. I know that several of the suppliers offer a few options for hanging scales for weighing lambs. For weighing fleeces, we use a postal scale. Sling: Only really necessary come lambing time. Use for carrying little lambs, and weighing. First Aid Kit and Injectables Most can be ordered online from Jeffers, PBS or other livestock supply companies. Digital thermometer Antiseptic scrub Disposable latex gloves Hoof trimmers Flashlight with extra batteries Frothy bloat treatment (for bloat and constipation in ruminants) Gauze dressing pads Hydrogen peroxide Lubricant for the thermometer (i.e., petroleum jelly) Oral syringe - Drenching gun (for dosing medications by mouth) Pocket knife Scissors (for cutting dressings) Self-stick elastic bandage, such as Vetrap Sterile saline solution (for rinsing wounds and removing debris from eyes) Syringes (without the needle, for flushing wounds, etc) Tweezers Udder ointment (We use Udder Comfort from PBS) Wire cutters Wound ointment/spray (Check the label if you plan to use the product for meat and dairy animals.) Hydrogen peroxide Injectable vitamins: Vitamin B complex fortified, Vitamin A, D, E and Vitamin C Syringes and needles. 18 and 20 gauge needles. 1/2, 3/4 and 1 inch lengths. BoSe (injectable seleium and E) is a must have. Get it from your vet. CDT vaccines Tri-iodine, or other strong iodine. A good Dewormer—You never want to be caught with a sheep that is suffering with a high parasite load and you have no way to treat it fast. Many dewormers are not available in the local feed store and must be ordered online. Find out which ones are effective for you (many are no longer effective due to parasite resistance) and always have it on hand. Sel Plex Selenium yeast. Ketonic, Sheep Nutri Drench or other similar product. (Lancaster Agriculture has many excellent products.) Rescue Remedy spray Portable (Temporary) Fencing: We use a lot of portable netted fencing. It is really necessary for practicing rotational grazing. We highly encourage all of you to practice MIG -- it is highly beneficial for your Icelandic sheep and for your pastures. I would recommend four to six rolls of netted fence to start. We use the longer rolls. I prefer the 42" height. Follow the links on the Resources page for fencing suppliers. So, this is a list of sheep stuff that will set you up pretty well for being prepared for your new flock. As you go along, you will probably find some additional things you think will we helpful in your situation.

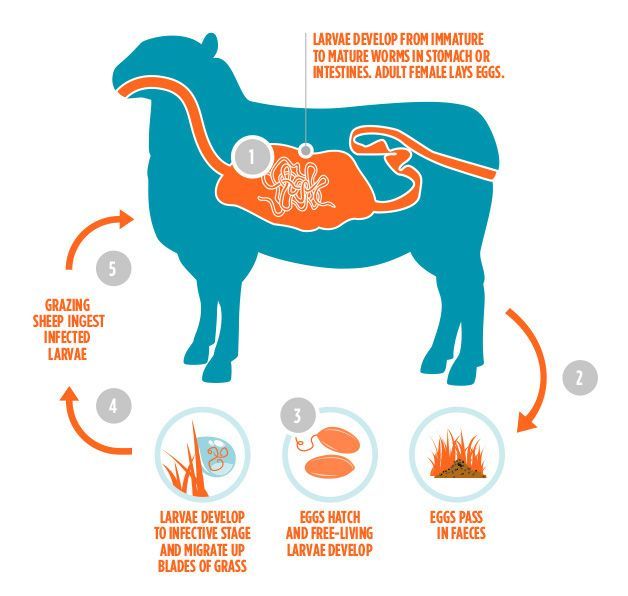

By Jean Duval, agronomist, M.Sc. January 1994 I would like to thank Christiane Trudeau of the McGill University Institute of Parasitology, Jean-Marie Boucher of the Centre d'Agriculture Biologique de la Pocatière and consulting agronomist Caroline Morin for their comments on the text. THE CONTROL OF INTERNAL PARASITES IN RUMINANTS Internal parasites in ruminants constitute a problem that returns periodically in almost all livestock herds. Recourse to synthetic dewormers is only a short-term solution. Animals that graze are always exposed to parasites and are thus constantly being reinfected; not to mention that routine deworming treatments delay the development of immunity in young animals. Moreover, certain parasites have developed a resistance to such deworming products as Benzimidazole, Levamisole and even Ivermectin because of too frequent use. Studies in New Zealand and Ireland indicate among other things that dewormers slow the decomposition of manure. A serious pest control program in organic farming begins with a good understanding of parasites and the implementation of preventive measures. The ultimate objective is to develop an animal production system where parasites may be present in small numbers but do not affect the health or performance of herds. Deworming treatments, whether administered using natural products or not, should therefore only be employed in emergency situations or, if using weaker products, as preventive maintenance. This document provides a description of internal parasites, methods to prevent their infestation and alternatives to conventional dewormers for ruminants. The section on botanical dewormers also includes information on other farm animals (pigs and poultry). GENERAL INFORMATION LIFE CYCLE OF PARASITES Knowledge of the life cycle and characteristics of parasitic worms is essential for anyone wishing to reduce their use of dewormers. Figure 1 shows the direct life cycle common to most parasites. Some parasites however have an indirect cycle, which involves a host animal. For example, the liver fluke (Fasciola sp.) spends part of its life in certain snail species before infecting ruminants. Table 1 presents the main classes of internal parasites, whereas Table 2 provides a list of the main internal parasites of ruminants and their characteristics. Internal parasites are most often worms (helminths) but can also be protozoa, which will not be covered here. Worms are generally specific to one organ, such as the abomasum, duodenum, and lungs. 1. Parasite-infested animal harbours adult worms... 2. The eggs produced by the female are deposited in pastures with fecal matter... 3. They develop into various larvae stages. 4. Animal is contaminated by absorbing L3 larvae or infesting larvae with the grass. 5. The larvae make their way to the alimentary canal where they develop and produce a new generation of adult male or female parasites. Figure 1 . Life cycle of internal parasites in ruminants Source: Rivard et Huneault (1992) Table 1 - Major classes of internal parasites ROUNDWORMS or NemathelminthesStrongyles Gastrointestinal worms Abomasum worms: Haemonchus, Trichostrongylus, OstertagiaDuodenum worms: Trichostrongylus, Nematodirus, Cooperia, StrongyloidesLarge intestine worms: Oesophagostomum, TrichurisSmall intestine worms or Ancylostomidae (hookworm): Ancylostoma, Necator, Bunostomum Lungworm or metastrongyles: Dictyocaulus, Metastrongylus, ProtostrongylusAscarids: Ascaris (duodenum) FLATWORMS or platyhelminthesCestodes (tapeworm): Taenia, Echinococcus, Moniezia (duodenum)Trematodes: Fasciola, Dicrocoelium (liver) Table 2 - Characteristics of main internal parasite genera in cattle, sheep and goats ParasiteDescriptionInfected OrganLife CycleSymptomsHaemonchusM: 10-20 mm red F: 18-30 mm red and whiteAbomasumIS: 4-6 days PP: 3 weeksAnemia, soft swelling under jaw and abdomen, weakness, no weight gainOstertagiaM: 6-9 mm, brown F: 8-12 mmAbomasumIS: 4-6 days PP: 3 weeksSame as Haemonchus and also lack of appetite, diarrheaTrichostrongylusM: 4-5.5 mm F: 5-7 mm light brownAbomasum, duodenumIS: 3-4 days PP: 2-3 weeksSame as Haemonchus and also diarrhea and weight lossCooperiared M: 5-7 mm F: 6-9 mmDuodenumIS: 5-6 days PP: 15-20 daysSame as HaemonchusBunostomum10-30 mmDuodenumIS: ? PP: 30-56 daysEdema, anemia, weight loss, diarrheaStrongyloides (young animals)4-6 mmSmall intestineIS: 1-2 days PP: 8-14 daysAnorexia, enteritis, diarrheaChabertiaM: 13-14 mm F: 17-20 mmLarge intestineIS: 5-6 days PP: 42 daysAnemia, diarrhea with bloodOesophagostomumM: 12-17 mm F: 15-22 mmLarge intestineIS: 6-7 days PP: 41-45 daysDark green diarrhea edemaProtostrongylusM: 16-28 mm F: 25-35 mmLungsIS: 12-14 days PP: 30-37 daysPneumoniaDictyocaulusM: 30-80 mm F: 50-100 mmLungsIS: 6-7 days PP: 3-4 weeksSticky nasal discharge, difficulty breathing, cough Legend: M = Males; F = Females; IS = Infectious stage: minimum number of days for parasite to reach infectious larvae stage (L3) after hatching of eggs; PP = Prepatent stage: period up to appearance of first eggs in dung after host is infected. ROLE OF PARASITES One may ask what the role of internal parasites is in nature. Do they reduce populations that are too large for the resources available? Overpopulation is often, if not always, inherent to agriculture. Or do parasites serve to cull the weaker animals, thus reinforcing a species' chances for survival? This is doubtful since it is generally not to the parasite's advantage to kill its host. Whatever the case, it is normal in nature to find internal parasites in animals. In a natural setting, ruminants, although in herds, are constantly moving from one grazing area to another. It is therefore rare that the soil and grasses they eat are highly contaminated. Since levels of infestation are rarely excessive, animals have a chance to develop immunity. The levels of infestation in goats and sheep that are raised in fairly natural settings tend to fluctuate with seasonal metabolisms without the animals being treated 25 . It has been observed in goats and sheep that the highest levels of parasites correspond to periods of change: change in location (e.g. buildings to pasture in the spring); change in diet or use of food (e.g. lactation to maintenance diet). This would indicate that internal parasites may play a role in helping animals get through periods of change and adaptation. THE BIODYNAMIC POINT OF VIEW The point of view of biodynamic practitioners is focused largely on the role parasites play in animal digestion 36 . They believe that gastrointestinal parasites play a role similar to earthworms in the soil; that they "aerate" the digestive system when it is overloaded by too much silage, grain or green hay. Since the roots of plants have the same effect as earthworms, biodynamic farmers add fodder roots (e.g. beets, carrots) to animal feed to replicate the role of parasites. SUSCEPTIBILITY AND IMMUNITY An animal without worms is not an ideal to strive for at any cost, at least not in organic farming. An animal that never has worms can not develop resistance and is thus extremely vulnerable when exposed to a parasite. Resistance or immunity is the ability to prevent or limit the establishment or subsequent development of worm infections. Tolerance is the ability to maintain good productivity despite infection. Contrarily, susceptibility to parasites is defined by how easily the animal becomes infected. Ideally, grazing animals - especially the youngest ones - should ingest parasites in small quantities so that they may progressively develop immunity. This does not apply, however, to all internal parasite species. Susceptibility according to species Most internal parasites are specific to one or two species. When they are found in other animals, it is usually only for a brief period. Certain parasite species common to several types of domestic animals have even developed more specific "breeds". Although there are just as many parasite species that can infect cattle, sheep or goats, sheep are the most susceptible to internal parasites because they graze close to the ground. Goats and sheep, whose manure is in pellet form, graze directly over their manure, which makes them more susceptible than cattle who do not have access to the grass under their pats. Also, cattle tend to avoid the less appetizing grass near the pats. Susceptibility according to age The age as well as the weight of animals determine susceptibility to parasites. Young animals do not have a great deal of immunity to parasites during their first year at pasture. The second year, they have partial immunity and, although they may appear healthy, they excrete many eggs. Adult animals are much less susceptible to most parasites, unless they are in poor living conditions. For example, it has been demonstrated that horses 15 years of age or older are rarely infected by strongyles 13 . Instead, parasites like Strongyloides are almost exclusively found in young animals. Other susceptibility Animals are sometimes kept in conditions that make them highly susceptible to parasites. In the case of a recently dewormed animal, internal parasites no longer exist. There is thus no equilibrium and such an animal put into a contaminated pasture may be seriously affected. Animals in poor condition (e.g.: recent illness, food shortages) are also highly susceptible. Genetic resistance There are breeds or lines of animals that are resistant or more tolerant to internal parasites. In New Zealand, herds of sheep resistant to internal parasites were developed from Romney sheep. The approach adopted by organic farmers in New Zealand is to over the years develop a herd that is increasingly resistant, using resistant rams only, and not ewes. DETECTION The first step in a pest control program is to assess the situation. The two methods used for this purpose are fecal counts and field counts. FECAL COUNTS Veterinary offices conduct fecal analyses. These consist in identifying the species of parasites present in the animal and counting the eggs of the parasites per gram of stool. Results of the analyses are often expressed in qualitative terms: absence of parasites, low, average or high levels. In all cases, it is important to identify the parasite. Two approaches may be used: Herd analysis Randomly selected feces are used to determine the general state of the herd. A minimum of three to five pats is required in the case of cattle. Ideally the stools should be collected at midday for the egg production is more uniform at this time 8 . Individual analysis Feces from a single animal are used by isolating the animal and collecting them first thing in the morning and then fresh stools during the day. The purpose of an individual analysis is to confirm that the symptoms observed in the animal are in fact caused by a parasite infection. Stool analyses have limits as methods for evaluating the situation. Certain species of parasites lay few eggs, others many. Some lay eggs only at certain times of the year or during a particular period in the ruminant's life cycle. The best way to benefit from fecal counts is to always perform them at the same time each year and preferably during critical periods, such as when the animals are put out to pasture or before bringing them in for winter. If the parasite level is high, two to four analyses will provide a better picture of the situation. Comparison from one year to another of analyses conducted during the same period will indicate if there is an improvement or not. Other instances where stool analyses are useful are, for example, when there is a change of pasture ground, when new animals arrive, or when there are animals who appear to be ailing or young animals that are not putting on weight. FIELD COUNT A field count is more difficult to do. In North America, it is mostly done as part of research programs. Samples that are representative of the grazed pasture must be collected, taking into account the height of the cut. In New Zealand, where this type of analysis is more common, it is considered with respect to sheep that if there are less than 100 larvae per 100 kg of grass there are neither economic losses nor drops in productivity 39 . PREVENTIVE MEASURES From the ecological perspective, serious problems with internal parasites indicate that changes in feed, field management or soil management are required. By changing the production method or by using preventive measures, it is not necessary to rely on dewormers too often. HERD MANAGEMENT An animal is better able to resist or tolerate internal parasites when its living conditions are good. Links between diet, particularly vitamins and minerals, and susceptibility to internal parasites have been established in certain cases. Vitamins A, D and B complex are the most important vitamins required by animals to develop resistance to internal parasites 23 . Nyberg and his coworkers, quoted by Quiquandon 31 , have established that a lack of cobalt promotes parasitism, since cobalt is the element used by animals to synthesize vitamin B12. Iron supplements are also very important where animals are affected by worms that drain the blood, like Haemonchus (worms in the abomasum) and Ancylostoma (intestinal worms). According to Lapage 23 , animals should always have access to mineral blocks to compensate for the mineral deficiencies in pastures. In barns, animals should be fed from feeders rather than directly from the ground to avoid contamination as a result of their mouths coming into contact with manure or bedding. At the New Zealand Pastoral Agriculture Research Institute, research is currently underway on how different foods affect resistance to parasites. Forage crops that contain condensed tannins, like trefoil, allow animals to better fight parasites than others that do not contain any, like alfalfa. The age at which young animals are weaned is an important factor in regard to parasite resistance. For example, it has been observed that milk-fed calves are distinctly less contaminated by Haemonchus, Cooperia and Oesophagostomum than weaned calves 34 . Milk does not have any effect, however, on Ostertagia and Trichostrongylus infections. Ideally, females should calve during periods when risk of contamination is low, so that young animals are exposed as late as possible to potentially contaminated pastures. In Northern parts of North America, the winter period seems most appropriate in this respect. All new arrivals to the herd should be quarantined for four to six weeks and dewormed if there is any doubt. PASTURE MANAGEMENT Pasture management that is designed to prevent internal parasites requires long-term planning. It is by varying such factors as the density and age groups of animals and the time and intensity of grazing that serious infections can be avoided. Animal density Overpopulation increases the concentrations of parasites. It is generally estimated that parasite infections increase with the square of the animal load per surface unit. Therefore, for a given parcel of land, parasite infestations are four times greater where animal density is doubled. Density varies depending on whether grazing is intensive or extensive. Where there is extensive grazing, Antoine 2 recommends less than 10 lambs/ha (varying according to context). Pasture rotation, or intensive grazing, consists in dividing the pastures into parcels of land of varying sizes called paddocks and frequently moving the animals from one paddock to another to optimize grass use. From a parasitic point of view, the objective is to not put the animals back into the same field until the risk of infection has diminished. Theoretically this means that parasitism will decrease if the number of parcels of land is increased or the rotation time is increased. Unfortunately, in practice, it appears difficult to diminish the parasitic load with intensive grazing. The lifespan of L3 larvae is in fact always greater than the time required between grazing periods for maximum grass use. Therefore, if one waits six weeks before returning animals to a lot, the quality of the grass decreases as well as the quantity of grass ingested by the animals, whereas the level of parasites only diminishes slightly. Grazing height About 80% of parasites live in the first five centimetres of vegetation. Parasite infection and multiplication are prevented by letting animals graze only 10 cm from the ground in a field where there are parasites. For new pastures, however, New Zealander Vaughan Jones 18 , an expert on intensive grazing, recommends having animals graze very close to the ground, so that the sun can dry the pats quickly and thus diminish the chances of survival of parasites brought in with the animals. A new pasture is considered a field where animals have not been grazing for a number of years. It may be a pasture seeded in the spring or a hay or silage field that is used as pasture after harvest. Grazing time The drier the grass, the more parasites will stay at the base of the plants. It is estimated that in wet grass, larvae can be found over 30 cm away from the pats, whereas they venture only a few centimetres away when the grass is dry. The risk of infection is greatly lowered by waiting until the dew has lifted or until the grass has dried after rain before putting animals out to pasture. The larvae of most parasites move to the tops of plants when light levels are low, that is, when the sky is overcast or at sunrise and sunset. They avoid strong light however. Limiting grazing time to when the sun is strong also diminishes the risk of infection. Since we know that the density of L3 larvae is generally at a maximum in the fall and at a minimum in the summer, it is preferable to limit grazing in highly contaminated fields to the summer months to reduce levels of ingestion. In the fall, the animals should ideally be put in a new pasture. Risks of infection from most parasites can be avoided in the spring by waiting until the end of spring to put cattle out to grass, and even later in areas where soil drainage is poor. In practice, this solution is not very satisfactory, both economically and ecologically, because it implies shortening the grazing season, which is quite short as it is in most northern regions, and feeding the animals more hay. Harrowing Pastures With respect to parasites, harrowing pastures is generally not recommended. The parasite eggs and larvae are in fact scattered throughout the pasture. This makes it impossible for the animals to graze selectively, that is, to graze around the pats. Harrowing would be appropriate, however, at the beginning of a dry period in a field that the animals will not be returning to for quite some time. Biodynamic practitioners have a different point of view. They consider that parasites proliferate in an environment that is nitrogen-rich and sheltered from light. They therefore recommend breaking up the pats to let in air and light. Grazing by age group Since the susceptibility of animals varies with age, it is logical to graze the younger animals in fields where parasite populations are very low. Organic farmers in New Zealand have established some rules to prevent internal parasites in lambs and ewes. Thus, in intensive grazing, lambs do not have access to paddocks or sections of a pasture already grazed by ewes or other lambs in order to prevent reinfection. Lambs should graze preferably in new pastures, hay or silage fields, or should be greenfed. Since sheep graze year-round in New Zealand, there is usually an increase in parasites in the spring, due to a drop in immunity in ewes after lambing. Parasite levels rise again at the end of the summer to early fall. Consequently, ewes do not go out to pasture until the lambs are weaned. After weaning, the ewes graze in a different part of the farm while alternate groups of lambs graze in another sector. These sectors are rotated each year. Another New Zealand technique is used to reduce parasite infection in calves. This technique consists in grazing the calves alone or in pairs on a rotating basis. The calves remain in the same lots all the time while the cows are rotated. Very good results have been obtained this way, even though there is no clear reason why this method works. Another common practice used with calves is to put them in a new pasture. To fight Ostertagia infection, for instance, the calves would be placed in an old field at the beginning of the season, then dewormed and brought to a parasite-free field in early July. In dairy herds, young cows can be slowly immunized by allowing them to graze in new pastures with two dry cows that serve as sources of infection. The ingestion rate of L3 larvae is therefore quite low, allowing for controlled infection and development of immunity. Multispecies grazing Producers who have more than one animal species (e.g. cattle and sheep) can alternate grazing of different animal species which, although not foolproof, can help to break the parasite cycles. Several parasite species cannot infect two different animal species. There are even certain species of worms that affect only a particular ruminant species. Cattle and sheep herds can be combined in three ways: (1) Graze the cattle to "clean" the pasture after the lambs have grazed. The cattle ingest a significant quantity of mature larvae from the lamb stools. If the cattle are allowed to graze the grass down to 3 to 5 cm from the ground, many parasites will be killed off from exposure to the sun; (2) Graze the cattle before the sheep to control pasture quality; (3) Graze the cattle and sheep together where vegetation is abundant. SOIL MANAGEMENT Deworming treatments have little effect if the animals are returned to the same larvae infested field. It is therefore important to clean the pasture as much as possible to reduce, if not eliminate, the parasites. Possible strategies for this are resting the land, planting, using amendments or fertilizers to reduce parasite populations, and improving drainage. Resting the land This consists in preventing the animals from grazing in the same field or paddock. Since freezing temperatures or droughts eliminate some infectious larvae, cold or dry periods can be relied upon to reduce or extend rest periods. A three-year rest period (short rotation) is required for a complete cleaning. Nematicide plants Mustard is an excellent nematicide plant and so are tagetes. For more information on the subject, consult the Agro-Bio synthesis entitled "Controlling nematodes with nematicide plants". Amendments and fertilizers Amendments that change the pH, the mineral balance or that create an environment which is inappropriate for parasites may help to clean the land. The choice of amendment or fertilizer depends on the type of parasite. According to Nunnery 26 : - Salt (sodium chloride) is appropriate for use against ancylostoma larvae such as Bunostomum. Salt must be used with caution on account of its deflocculating properties in clay soils, and should not be used on a regular basis. - Liming and acidification with copper sulphate are appropriate against liver fluke (Fasciola), which is transmitted by snails. - Copper sulphate is also effective against the Dictyocaulus lungworm. Mackenzie 25 recommends applying 23 kg/ha of copper sulphate mixed with 90 kg/ha of sand in this case. Manure management Manure to be used for spreading may be filled with parasite eggs and larvae. Composting is a good way to clean manure as the larvae and eggs of nematodes are destroyed at temperatures as low as 32 to 34C. They are killed in as little as one hour at 50C, and in less than four hours at 44C. It is important, when turning the compost over, to ensure that the outer layer which has heated less, be mixed towards the middle of the pile. Composting is a useful technique before manure spreading in the case of truly dangerous parasites like lungworm. Bedding is also important. For example, it has been demonstrated that eggs and larvae are all killed in horse manure mixed with straw bedding, as well as horse manure mixed in a one to four ratio with cow manure 3 . Parnell 28,29 studied the effects of adding different nitrogen fertilizers to, among others, sheep and horse manure. Urea was the most efficient nitrogen fertilizer for cleaning manure, with a required proportion of 1:125. Kainite (sulphate of potassium and sodium) was the most efficient non-nitrogen fertilizer to add to manure, with a required proportion of 1:23. In practical terms, Parnell suggested applying these substances to the surface only, since temperatures in the middle of the manure pile would be high enough to eliminate the parasites. Improving drainage Pastures or parts of pastures that remain wet for long periods are an ideal environment for the survival of internal parasite larvae. Standard drainage of a field may reduce the larvae's chances of survival and extend grazing periods. Localized drainage of wet patches prevents infectious larvae from persisting in an otherwise clean field. It is also important that cattle watering areas be situated in well-drained places with gravel or even cement added. Animals must be prevented from accessing swamps or streams at all costs because of the parasitic risks, the damage the animals cause to these areas and the risks of pollution. PARASITE CONTROL METHODS GENERAL INFORMATION When to deworm It is crucial to choose the right time to carry out deworming treatments. At a certain stage of their development inside the animal, some parasites embed themselves in the mucous membranes and enter hypobiosis (e.g. Ostertagia). They are largely inactive at this stage and relatively harmless to the host. Deworming treatments have little or no effect when performed at this time. A sensible conventional practice to employ against parasites is to perform a first treatment three weeks after the animals have been put out to pasture and a second treatment three weeks later. The first treatment serves to prevent infection by infectious larvae (L3 stage) - before the new adults formed inside the animals have begun to lay eggs profusely and contaminate the pastures. When the second treatment is given, typically in early July, a large portion of the infectious larvae in the pastures will have died as a result of the hot dry conditions. According to a traditional French practice, deworming treatments are performed preferably when there is a new moon. The worms are more active at this time and therefore easier to dislodge. On the other hand, Rudolf Steiner, the father of biodynamic agriculture, recommends performing deworming treatments during a full moon. Lapage 23 suggests deworming at the approach of dry or cold periods to benefit from the sterilizing effect of these factors. Which animal to deworm Antoine 2 recommends deworming: - susceptible animals about three weeks after being put out to pasture; - grazing companions of heavily infested animals; - all animals in heavily grazed pastures, in the summer, after a few hot and very humid nights. How to deworm All deworming treatments involving natural products should ideally be preceded and followed by a fasting period, except in the case of nursed young animals. Animals should not be fed for a period of 12 to 48 hours before the treatment and another 6-hour period afterwards. A laxative diet or purge should then follow. Castor oil is appropriate for non-ruminants, and a saline diuretic or sodium sulphate and magnesium for ruminants. Liquid deworming treatments that animals do not willingly ingest can be administered using a funnel and a flexible tube put down the animal's throat, or a "gun" designed for this purpose. In the case of milking dairy cows, it is difficult to fast the animals. Subsequently, it may be simpler to lighten their diet by not using silage or concentrates rather than to fast them. Note that putting animals out to pasture in the spring has a laxative effect on them. It seems appropriate therefore to treat the animals at that time. For confined animals, a radically different way to deworm is to spray essential oils using an atomizer in order to fill the air with aerosols that have anthelminthic (synonym with dewormer) properties. Gape-infested pheasants have successfully been treated with pyrethrum oil, goosefoot oil and roto-resin using that method 15 . BOTANICAL DEWORMERS Several plants have anthelminthic properties, and were in fact a part of the traditional husbandry before synthetic dewormers were commonly adopted. In Québec, for instance, it was common practice to feed evergreen branches (pine, spruce or fir branches) to sheep. Although based on conventional wisdom, veterinary research zeroed in on deworming plants, also called anthelminthic plants, particularly before the Second World War in Western countries then, subsequently, mainly in Eastern countries and India. There is reliable data available on the effects of several plants or plant extracts on certain parasites, enabling us to know the limits of these substances. Allopathy versus homeopathy Several of the dewormer plants mentioned below may cause side effects in animals. The most powerful natural dewormers are often potential poisons. It is therefore important to follow the indicated dosages. A way to avoid side effects is to administer these plants in the form of homeopathic preparations. The advantage of homeopathic remedies is that they do not require a fasting period beforehand and laxative diet after the treatment. Garlic Garlic is a common plant dewormer that is easy to find. It is known to be active against, among others, Ascaris, Enterobius and, of particular interest for ruminants, against lungworm in general 1 . It must be used, however, as prevention (prophylaxis) rather than as treatment or with other products. In fact, garlic does not prevent the production of eggs but prevents the eggs of certain parasites from developing into larvae 5 . In the ninth century, in Persia, Avicenne recommended the use of garlic as an additive rather than as a dewormer alone. Garlic is incorporated into certain commercial homeopathic or allopathic dewormers, but always with other plant-derived substances. The numerous therapeutic properties of garlic come mainly from its high sulphur content. Garlic can be administered in several ways: Fresh : Fresh minced garlic proved to be clearly more efficient than garlic extracts for controlling internal parasites in carp 30 . Using fresh garlic is ideal although not necessarily the most practical on a day-to-day basis. The leaves and bulbs may also be used. If the animals do not want to eat the leaves whole, they may be cut into small pieces, mixed with molasses and bran, and shaped into small balls. The bulbs may be grated and mashed with molasses or honey and flour. Garlic may also be planted directly in the pastures in such way that the animals have access to it as needed. Powder : The most practical way to administer garlic is undoubtedly to add powdered garlic to animal feed. Powdered garlic can be bought at a reasonable cost in bulk from major food manufacturers (e.g. McCormick, Quest International, Griffith Laboratories, etc.). Pills : This is a method that is useful only for very small herds. Two or three pills of four grains is the required daily dosage for one sheep. Juice : British herbalist Grieve 16 suggested using garlic juice or garlic milk as a dewormer. Garlic milk is made by boiling bulbs mashed in milk. Some researchers recommend, however, not boiling garlic as this reduces its effectiveness against parasite eggs and larvae. Mother tincture : Garlic mother tincture is given in dosages of 20 drops/day/10 kg of live weight. In the case of dairy animals, it is preferable to feed them garlic during or immediately after milking so that the milk does not pick up the taste. Wormwood Wormwood, as its name suggests, is an excellent dewormer. Many wormwood species have deworming properties. - Common mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris) is effective against Protostrongylus, Dictyocaulus and Bunostomum. Sheep, goats and fowl readily consume it 10 . - Common wormwood (Artemisia absinthium) must be used with caution as it may be dangerous if used regularly or excessively. The dried and crushed flowers may be used or steeped in cold water. De Baïracli-Levy 9 suggests the following recipe for dewormer balls: four teaspoons of cayenne pepper powder, two teaspoons of powdered common wormwood mixed with honey and flour. - Eurasian wormwood (Artemisia cina) is a desert plant that is used to make santonin and the homeopathic remedy Cina, which are used as dewormers. Santonin is extracted from the dried buds of the plant. The buds are then treated with liquid lime and dried again. Santonin acts against most parasites except Echinococcus. It must be used with caution, however, because even in small doses it causes side effects, particularly eye problems. Homeopathic Cina may be acquired as mother tincture, administered in 2 to 3 drops/10 kg, morning and evening for 3 weeks, or in granules in different dilutions. Consult a homeopathic veterinarian for more information. - The dried, powdered shoots of Artemisia herba-alba wormwood (a species common to North Africa) administered in dosages of 10 to 30 g per goat proved highly effective against Haemonchus contortus 17 . - Tarragon (Artemisia dracunculus) also has deworming properties. Several wormwood species grow wild in North America. It might be a good idea to let these plants grow along pastures where the animals can eat them as needed. Wild ginger Wild ginger or snakeroot (Asarum canadense) grows in wooded areas. This plant is very similar to European wild ginger which was used as an anthelminthic purge for cattle and horses. The dosage per animal is 20 to 30 g of the aerial parts of snakeroot mixed with wet bran. Wild ginger also has antibacterial properties. If planning to use this plant, remember that wild ginger, as well as wild garlic, require several years to reproduce. Goosefoot Chenopodium ambrosioides or goosefoot is a widely used dewormer plant. In Brazil, the plant is fed directly to pigs to deworm them. The powdered seeds serve as a dewormer and insecticide. The Japanese make a dewormer tea with the leaves. Oil from the goosefoot, although highly efficient, is extremely toxic. Human consumption has often led to strong side effects (nausea, headaches) and even death in some cases. It is better to use less hazardous substances than goosefoot oil. Conifers Conifers, like garlic, are undoubtedly more indicated in prophylactic form, that is, in small quantities in daily food, rather than as a curative treatment. In Russia, Ascaris infestations in pigs were reduced by giving them 1 to 2 kg of pine needles each day for 2 to 4 weeks 39 and mixtures of conifer needle powder and sulphur or vitamins were also used successfully against internal parasites. In practical terms, it is easier to use pitch, also called turpentine, extracted from pine and various other conifers. Turpentine spirits are a byproduct of turpentine distillation. Cabaret 6 prescribes 50 to 100 ml of spirits produced from turpentine distillation with a triple volume of castor oil against ruminant liver fluke and horse strongyles. A mixture of linseed oil (edible and not the variety found in hardware stores) and turpentine spirits constitutes a powerful dewormer, but which must be used with caution. If turpentine enters the respiratory system it may cause the spasmodic closure of the mouth. It is therefore preferable to use rolled oats to soak up the turpentine before feeding it to animals. For one lamb, 10 to 15 drops of turpentine spirits are mixed with an ounce of linseed oil and a pinch of ground ginger; for an adult sheep, 80 drops in two ounces of linseed oil. Common juniper (Juniperus communis) has deworming properties, notably against liver fluke. Sheep enjoy juniper berries and deer graze on the plant. It might be interesting to allow restricted access to woodlands where the animals can find conifers to eat if they wish. Crucifers (mustard family) White or black mustard seeds in the amount of 2 ounces per lamb is a safe dewormer, and it is recommended allowing the herd access to mustard in the pasture or elsewhere. In India, some cattle farmers use mustard oil against parasites in the amount of 100 to 150 g per day for one week. Mustard oil is more of a laxative than a dewormer, which is nevertheless useful in eliminating some parasites. The following crucifers are dewormers and may be added to animal feed: radishes, raw grated turnips or horseradish, nasturtium seeds. Cucurbits The seeds of squash, pumpkins and many other vine crops contain a deworming compound called cucurbitacin that is more or less active depending on the parasite 12 . The seeds may be fed directly to animals as the Canadian pioneers once did, but it is better to extract the main ingredient using water, alcohol or ether, for an effect that is similar to that of pumpkin seeds. Aqueous extracts from squash seeds (dilution 1/50) are effective against Haemonchus contortus 38 . Pumpkin seed dewormer 24 - Shell and grind up the pumpkin seeds (or buy them at a grocery store). - Mix 500 g of the seeds with three litres of water. - Simmer (do not boil), while stirring, for 30 minutes. - Let cool 30 minutes. - Filter through a cloth, squeezing to remove as much juice as possible. - Reduce over low heat to 150-200 ml. - Make sure to remove oily scum. - Refrigerate. Fern The rhizomes and young shoots (fiddleheads) of the male fern (Dryopteris filix-mas) have deworming properties that have long been recognized in Europe, among others, against tapeworms (Taenia). The North American equivalent of the male fern is the evergreen shield-fern (Dryopteris marginalis). Although in the past, ether extract of the male fern was widely used against the liver fluke in the British Isles, the male fern does not give satisfactory results in the case of the Dicrocoelium fluke in sheep 14 , nor against Echinococcus in dogs. The success of fern is enhanced by using fresh material and mixing it with glycerine. The male fern must be used with caution because it is toxic in high doses. In humans, for instance, it can cause headaches and nausea; the maximum dose is 7 g per adult. Lupine A diet made up entirely of freshly cut, lightly salted, lupine is a good dewormer that works against a large number of intestinal worms in pigs, including Trichuris (100% efficient), Strongyloides (66% efficient), Ascaris (50% efficient) 7 . Lupine is equally efficient against Parascaris and Strongylus in horses. It is important not to give free access to lupine, otherwise symptoms of poisoning may occur. Nuts Several vegetable species produce nuts that have anthelminthic properties, but unfortunately it is mostly tropical species like areca and cashew shells that are used. The fresh sap of the hazelnut (Corylus) is highly effective against Ascaris 22 . Umbelliferae Carrot seeds (Daucus carota), either wild or cultivated, are dewormers, as are teas made with the roots. A mixture of anise, cumin and juniper seeds is effective against Dictyocaulus lungworm in calves. Fennel leaves and seeds are also used as dewormers; the oil is a dewormer but very toxic too. In a central Asian area of the former USSR, it is common practice to graze sheep infected with Haemonchus in pastures where there are giant fennel (Ferula gigantea) and other Ferula species 42 . The worms are eliminated after two or three days and the plant is grazed for roughly 20 days. In many parts of North America, carrots and wild parsnips that grow abundantly along fields and roads could probably be used in the same way. Pyrethrum Pyrethrum (Chrysanthemum cinerariifolium) is commonly used as an insecticide in agriculture. It also has anthelminthic properties. As a dewormer, it is administered in powder form in animal feed. It may be safely used for warm-blooded animals, unless it is injected. In this case, it must be mixed with oil and the necessary precautions taken. Pyrethrum is 100% effective against ascarids in chickens, in the amount of 200 mg/bird using 0.8% pyrethrum 32 . A complete cure was obtained against Ascaris in chickens, by giving them pyrethrum powder (concentration unknown), using 2% of the ration for 7 days 44 . Pyrethrum is also useful against strongyles in horses, in the amount of 3.5 mg/kg of live weight 35 . For more information on the veterinary uses of pyrethrum, see Urbain and Guillot 41 . Although a Mediterranean plant, pyrethrum may be cultivated easily in many places. For more information on pyrethrum culture, see the Agro-Bio synthesis entitled "Home Production of Pyrethrum", available at EAP. Tobacco Tobacco and its derivatives (nicotine, nicotine sulphate) have been used as dewormers, particularly for fowl. With other farm animals, the mortal dose is practically the same for the worms as for the animals themselves! Tansy Tansy seeds (Tanacetum vulgare) are used against Nematodirus in sheep 27 . The oil from the flowers is also anthelminthic. An aqueous extract of tansy flowers and leaves is 100% effective in eliminating Ascaris from young horses and dogs, in the amount of 0.5ml/kg live weight in two doses administered one day apart and preceded by a one-day fast 19 . One kilo of leaves and flowers produces about one litre of extract. Cows and sheep consume fresh tansy easily, but goats, horses and pigs are not really fond of it. Other plants Blackberries, raspberries, and young ash and elder shoots are also other plant species with deworming properties that should be accessible in pastures. According to Cabaret 6 , beech creosote is used against lungworm in ruminants. The following plants, which grow naturally or may be cultivated in most of North America, are listed by Duke 11 as having deworming properties: - Yarrow (Achilea millefolium), which is highly toxic to calves; - Sweet flag or calamus (Acorus calamus); - Agrimony (Agrimonia); - Roots or root infusions of Indian hemp (Apocynum cannabinum); - Calendula (Calendula officinalis); - Hemp (Cannabis saliva); - Blue cohosh (Caulopyllum thalictroides); - Lady slipper root extract (Cypripedium calceolus); - Sweet gale or bog myrtle (Myrica gale); - Pokeweed (Phytolacca americana); - Common knotgrass (Polygonum aviculare); - Rue (Ruta graveolens); - Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis); - Savory (Satureja montana); - Skullcap (Scutellaria lateriflora); - Skunk cabbage or skunk weed (Symplocarpus foetidus); - Nettle (Urtica dioica) seeds and roots; - Valerian (Valeriana officinalis); - Verbena (Verbena officinalis); - Periwinkle (Vinca minor). A large number of tropical plants, and even some types of marine algae, also are reputed to have deworming properties. Mixes The commercial "natural" dewormer preparations, whether they are allopathic or homeopathic, are often mixes of different types of vegetation. The purpose of these mixes is to expand the range of action and, in some cases, they act, synergistically. Often, both tropical plants and those from temperate climates are included. Homeopathic laboratories each offer their own mixes, also called complexes. A list of major homeopathic laboratories is presented in the Useful Addresses section. OTHER DEWORMERS Diatomaceous earth Diatomaceous earth is made from the remains of fossilized marine algae called diatoms. The product is mined and reduced to powder form. This powder acts as tiny pieces of glass that tear the shells of insects and other arthropods. Many farmers add diatomaceous earth to the rations of their animals, among others, because it contains minerals and is relatively inexpensive. Some claim that diatomaceous earth acts as a dewormer when added on a regular basis in the amount of 2% of the ration. Scientific tests on the subject are limited however and opinions of farmers are contradictory. Moreover, diatomaceous earth has no effect on lungworm and is not very appetizing. It may also be a lung irritant. Given that the level of dust is already quite high in barns, diatomaceous earth does not seem appropriate when the animals are fed indoors. The main motivation for adding diatomaceous earth to rations should not be to control internal parasites. If it is to be used, it is important to use non-calcined diatomaceous earth and without additives for insecticide use. See the Useful Addresses section for the address of a supplier of diatomaceous earth for animal use. Surfactants Many American farmers use Shaklee's Basic H surfactant as cattle dewormer with success. However, the company does not endorse this use of the product. Also, the organic certification standards do not always allow its use because the exact nature of the product is a trade secret, although we know it is based on two soybeans enzymes. Grazier Joel Salatin from Virginia gives the product to his cattle through water at a rate of 1 cup of Basic H per 100 American gallons of water (a quarter cup into 100 litres) . He confines the animals for two days to make sure all the animals get it. Treatment is repeated 6 times a year, and costs less than 50 cents per head. Copper sulphate Copper sulphate, a mineral substance that already meets organic farming specifications for plant production, has a strong deworming action against certain parasites, particularly Haemonchus contortus and Trichostrongylus axei, which affect the abomasum. Copper sulphate is administered in a 1% solution in water, in the amount of 50 ml per lamb or 100 ml per adult sheep, and 30 ml/22.5 kg of live weight for calves to a maximum of 100 ml. This dewormer may be administered with a funnel and flexible tube. Treatment is given in the morning before the animals have eaten, followed by castor oil one half hour later. It is important not to feed animals for two hours following treatment because of poisoning risks. Others Peroxide and charcoal also have deworming properties according to some practitioners and salesmen. There is insufficient scientific data however to support these claims. CONCLUSION As to conclude, the following points can be highlighted from this review on alternative internal parasites control: - Parasite control starts with good knowledge of the parasites and how they affect livestock. - Susceptibility and resistance to internal parasites in animals is affected by several factors including the season, the age of the animals, nutrition, and pasture management. - Fecal counts are worthwhile to detect the types and number of parasites affecting the herd or an individual. These should be done in critical periods such as spring and fall. - As prevention, animals should not be allowed to graze when pastures are wet. Young animals should preferably be put in new pastures where parasite levels are low. Manure should be composted and soil drainage improved where needed. - Deworming can be done when the animals are put out to pasture and again three weeks later. Deworming with natural products should be preceded and followed by a fasting period except in the case of homeopathic remedies. - Garlic and conifers are good as prophylactic dewormers for regular use. Powdered garlic is easily obtained in bulk. - More potent botanical dewormers include wormwoods, snakeroot, cucurbits, umbelliferae and tansy. Goosefoot, fern, lupine and tobacco have serious side-effects that discourage their use. - Homeopathic remedies are easy to use, do not require fasting and can be found easily. Combinations of different homeopathic remedies offered by homeopathic laboratories have a good range of action against parasites. - Other products used as dewormers are diatomaceous earth, charcoal, peroxide and surfactants such as Shaklee's Basic H. There is no scientific evidence for the effectiveness of these products as dewormers, but many farmers use them and swear to their validity. Alternatives to the utilization of synthetic dewormers exist to control internal parasites in ruminants. As is often the case in organic farming, we should aim not to eliminate these pests but to learn to coexist with them. BIBLIOGRAPHY 1. Anonymous. 1953. Garlic as an anthelmintic. Veterinary Record, 65(28):436. 2. Antoine, D. 1981. En élevage biologique faut-il déparasiter les animaux? Nature et Progrès, October/November/December 1981:12-16. 3. Antipin, D.N. 1941. [Research on deworming methods for horse and cow manures]. Vestnik Selsk. Nauki Veterinafiya, 1941 (2):42-56. 4. Baker, F.H. and R.K. Jones. 1985. Proceedings of a conference on multispecies grazing. Winrock International Institute for Agricultural Development, Morrilton, Arkansas. 5. Bastidas, G.J. 1969. Effect of ingested garlic on Necator americanus and Ancylostoma caninum. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 18(6):920-923. 6. Cabaret, J. 1986. 167 plantes Pour soigner les animaux. Editions du Point Vétérinaire, Maisons-Alfort, France. 192 pages. 7. Chebotarev, R. S. 1956. [The use of some fodder plants in the control of parasitic infections of farm animals]. Problemi Parazitologli, Transactions of the Scientific Conference of the Parasitologists of Ukrainian SSR, pages 194-197. 8. Cornils, W. 1935. Systematische Untersuchunger uber Strongylideneier und Strongyliden im Kot und Darminhalt des Pferdes. Berlin Dissert. 43 pages. 9. De Baïracli Levy, J. 1973. Herbal handbook for farm and stable. Faber and Faber, London. 10. Deschiens, R. 1944. Action comparée de la tanaisie et de l'armoise sur les formes larvaires de nématodes parasitaires et saprophytes. Bulletin de la société de Pathologie Exotique, 37(3/4) :111 -125. 11. Duke, J.A. 1985. CRC Handbook of medicinal herbs. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, 677 pages. 12. Forgacs, P., J. Provost and R. Tiberghion. 1970. Etude expérimentale de l'activité anthelminthique de quelques cucurbitacines. Chim. Thér., 5(3):205-210. 13. Foster, A.O. 1937. A relationship in equines between age of host and number of strongylid parasites. Am. J. Hyg., 25:66-75. 14. Guilhon, J. 1956. Recherches sur le traitement spécifique de la dicrocoéliose ovine. Recueil de Médicine Vétérinaire, 132(10):733-749. 15. Guilhon, J. and J.P. Petit. 1960. Traitement de la syngamose des faisandeaux par les aérosols anthelminthiques. Compte-Rendu des Séances de l'Académie d'Agriculture de France, 46(7):1017-1020. 16. Grieve, M. 1971. A modern herbal. Volume 1. Dover, New York. 427 pages. 17. Idris, Um El A.A., S.E.I. Adam and G. Tartour. 1982. The anthelmintic efficacy of Artemisia herba-alba against Haemonchus contortus infection in goats. National Institute of Animal Health Quarterly, Japan, 22(3):138-143. 18. Jones, V. 1993. Grazing to control worms. The New Farm, 15(7):52-53. 19. Karamisheva, E.N. 1956. [Treating Parascariasis in foals and ascariasis in dogs with tansy]. Veterinariya, 33(12):29-30. 20. Kidd, R. 1993a. Roundup roundworms. The New Farm, 15(1):6-8. 21. Kidd, R. 1993b. Control parasites ornanically? The New Farm, 159(7):7-11. 22. Krotov, All. and D.G. Timoshin. 1957. [Trials of new preparations of vegetable origin against ascaridiasis in catsl. Meditsinskaya Parazitologiya i Parazitornie Bolezni, Moscow, 26(1):87-92. 23. Lapage, G. 1959. Mönnig's veterinary helminthology and entomology. 4th edition. Baillière, Tindall and Cox, London. 511 pages. 24. Lys. P., J Adès and Y. Badre. 1955. Essais sur les propriétés anthelminthique des graines de courge. Revue Médicale du Moyen-Orient, 12(3):339-340. 25. Mackenzie, D. 1967. Goat husbandry. Faber and Faber, London. 26. Nunnery. J. 1953. The control of internal parasites by the application of chemicals to the soil. Auburn Veterinarian, Alabama, 10(1):48-51. 27. Papchenkov, N.Y. 1968. [Tanacetum vulgare seed and naphtaman against Nematodirus infections in sheepl. Veterinarya Mosk., 45(8):48-49. 28. Parnell, l.W. 1937. Studies on the biodynamics and control of the bursate nematodes of horses and sheep. IV. On the lethal effects of some nitrogenous fertilizers on the free-living stages of sclerostomes. Canadian Journal of Research, Section D, 15(7):127-145. 29. Parnell, l.W. 1938. Studies on the biodynamics and control of the bursate nematodes of horses and sheep. V. Comparisons of the the lethal effects of some nonnitrogenous fertilizers on the free-living stages of sclerostomes. Canadian Journal of Research, Section D, 16(4)73-88. 30. Pena, N., A. Auro and H. Sumano. 1988. A comparative trial of garlic, its extract and ammonium Potassium tartrate as anthelmintics in carp. J. of Ethnopharm., 24(2-3): 199-203. 31. Quiquandon, H. 1978. 12 balles pour un veto. Tome II. 1ere partie. Éditions Agriculture et Vie. 239 pages. 32. Rebrassier, R.E. 1934. Pyrethrum as an anthelminthic for Ascaridia lineata. J. Amer. Vet. Med. Ass., 84:645-648. 33. Rivard, G and G. Huneault. 1992. Les parasites internes des bovins de boucherie. Bovins du Québec, August 1992:6-11. 34. Rohrbacher, Jr. G.H., D.A. Porter and H. Herlich. 1958. The effect of milk in the diet of calves and rabbits upon the development of trichostrongylid nematodes. Am. J. of Vet. Res., 19(72):625-631. 35. Rueda, E.A. 1954. [Comparison of pyrethrum and phenothiazine as anthelminthics anainst strongyles in horses]. Rev. milit. B. Aires, 2:147-152 and 154-156. 36. Salatin, J. 1994. Using Shaklee Basic H soap. Stockman Grass Farmer, 51(11):27-28. 37. Selinger, L. 1984. Cours d'élevage bio-dynamique. Mouvement de culture biodynamique, Huningue, France. 26 pages. 38. Sharma, L. D., H.S. Bahga and P.S. Srivastava. 1971. In vitro anthelmintic screening of indegenous medicinal plants against Haemonchus contortus of sheep and goats. Indian J. of Animal Research, 5(1):33-38. 39. Slepnev, N.K. 1967. [Use of some plants in the control of ascariasis in pigs]. Vetrinariya Moscow, 44(6):61-62. 40. Stieffel, W., J. Niezen and N. Thomson. 1992. Investigations into the control of intestinal parasites in lambs without the use of conventional anthelmintics. Pages 219 to 228 In Boehncke, E. and V. Molkenthin. 1992. Alternatives in animal husbandry. Proceedings of the International Conference on Alternatives in Animal Husbandry, Witzenhausen, 22-25 July 1991, Kassel University, Germany. 41. Urbain, A. and G. Guillot. 1931. Sur les pyréthrines et leur emploi en médecine vétérinaire. Rev. Path. Comp., 31 :493-502. 42. Utyanganov, A. A. and K.M. Yumaev. 1960. [The anthelmintic properties of Ferula plantsl. Veterinariya, 37(9):40-41. 43. Wall, R. and L. Strong. 1987. Environmental consequences of treating cattle with the antiparasitic drug ivermectin. Nature, 327:418-421. 44. Zarnowski, E. and J. Dorski. 1957. [Treatment of Ascaridia infestation in fowls]. Méd. Vét., Varsovie, 13:387-393.

For new flock owners, the thought of giving injections can be daunting. Willingness to do your injections will save you a great deal of money on vet bills, though. As a new shepherd/ess, a good option would be to have the vet come once to show you how to do the injections, both intramuscular and subcutaneous. Then, you will have confidence to do future injections on your own. Below, you will find links to a couple of sites that outline pretty well how to give injections in sheep or goats. How to give injections Giving Injections